On 24 December 1968, an important photo was taken. It was the first colour image ever of the Earth captured all in one frame. Humanity had seen sunrise on the horizon countless times before, it had seen moonrise on the horizon countless times before. But this photo captured Earthrise.

The astronauts aboard Apollo 8 – Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders – were the first people to orbit the Moon. Few people, if any, have been more alone than those three men were on the far side of the Moon, with radio contact with Earth blocked off. As the craft finally emerged from the dark side after more than 30 minutes, the control room erupted in cheers upon reception of a signal carrying the voice of Jim Lovell. As the Public Affairs Officer remarked: “The unmanned Lunar Orbiter spacecraft traversed the Moon perhaps over 10,000 times, but this is the first that a man aboard reported to his compatriots here on Earth.”

Apollo 8 orbited the Moon ten times in total, and the astronauts aboard had instructions for what to capture photos of on their journey – lunar terrain, and each other. The man behind the camera, Bill Anders, later said: “It didn’t take long for the Moon to become boring. It was like dirty beach sand. Then we suddenly saw this object called Earth. It was the only colour in the Universe.” They were never told to look for the Earth. As the spacecraft rounded the Moon for its fourth time and the planet swept into view, Anders looked up and snapped one of the most famous photographs in history.

“Then we suddenly saw this object called Earth. It was the only colour in the Universe.”

Bill anders, apollo 8 astronaut

But Earthrise didn’t immediately become a cultural touchstone. The first photograph of Earth from very far away was bestowed cultural, philosophical, and environmental significance many years after when Time magazine featured it as an era-defining photograph, and NASA put a recreation of it on a commemorative stamp. Earthrise was the first opportunity the public had of seeing our planet sitting out in the lonely darkness with only the lunar surface as a foreground. Looking back, it feels strange – wrong, almost – that not much was thought of it when it was taken. The overwhelming majority of humans to have lived on this planet never saw it like this.

Earthrise kickstarted a new age in humanity’s relationship to our home. We got to see the beauty and fragility of this living rock, steeped in the all-consuming blackness of space. Seeing images of the Earth from above is so routine now that it is easy to forget how great an achievement those images are. We figured out how to overcome terrestrial gravity, and to capture the light from our one true power source bouncing off of our home planet up towards our manmade satellites. It is a testament to human engineering and perseverance that we have managed to take such photographs. It is equally as impressive that we’ve taken so many that we don’t even bat an eye when we see them anymore.

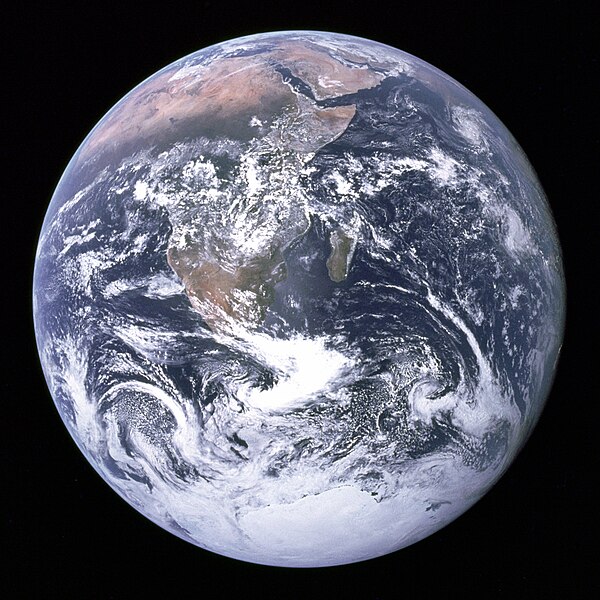

It was four years later, on 7 December 1972, that we managed to capture the complete shape of the Earth in the light. Earth had emerged from the shadow that it had once been shrouded in. The Blue Marble is exactly what comes to mind when you picture Earth from space. No wonder: it’s speculated to be the most widely distributed image ever.

Taken by the crew of Apollo 17, The Blue Marble is breath-taking in its majesty, with the continent of Africa sprawled among the blue and swirling white and the entire planet looking indeed like a celestial marble carelessly tossed onto the cosmic table. But another remarkable thing about this image is that it is the only one of its kind that we had for 43 years after it was taken. This full, unobscured view of Earth went un-replicated until 2015.

Very few people have had the privilege of seeing Earth from space. Many of those who have report a deeply impactful experience. There are few things more likely to instil in you a deep understanding of our common destiny than the sight of our lonely home wandering through space. We are all, quite literally, headed in the same direction. It was that feeling of human solidarity that Al Gore seized upon when he saw Blue Marble. Gore was Vice President to Bill Clinton between 1993 and 2001. A renowned environmentalist, he ran to succeed Clinton in 2000 but was beaten by the narrowest and most questionable of margins by George W. Bush in an infamous election that was settled by a Supreme Court case concerning potential miscounts in Florida. A few hundred votes in the right places, or perhaps even a recount, would have handed Gore the presidency. The last 20 years of environmental policy may have looked very different had that happened, as would the story of Gore’s dream of a spacecraft that would record Earth from space. He envisaged an uninterrupted livestream of Earth to boost environmental awareness, along with scientific equipment that could measure the albedo affect and changes in the Earth’s atmosphere in real time. The spacecraft took on many names, including at one point GORESAT, but eventually settled into the name DSCOVR, the Deep Space Climate ObserVatoRy.

Shortly after the 2000 election and the inauguration of Gore’s opponent, the spacecraft’s mission was put on hold and then rescheduled to launch with the 28th flight of Space Shuttle Columbia in 2003. It was removed from the payload at the last second but that is not the reason that we remember the flight: this was to be an ill-fated mission. Upon re-entry into the atmosphere, the shuttle disintegrated as atmospheric gases penetrated the heat shield and destroyed the internal wing structure. The lives of all seven crew members were tragically lost.

It was more than a year until the shuttle program launched again but the DSCOVR spacecraft was put on hold indefinitely. When the Obama administration came in in 2009, NASA reaffirmed its commitment to launch the spacecraft and, many years of bureaucracy later, it was agreed that SpaceX would transport DSCOVR to its destination in 2015. That destination was a Lagrangian point, informally known as a “parking spot in space”.

Lagrangian points are the stable solutions of three-body orbital systems in which the third body (the spacecraft) is of negligible mass compared to the other two (the Earth and the Sun). That means that at these particular points, the spacecraft will stay in place relative to the Earth due to the combined gravitational pull of the Earth and Sun. DSCOVR was headed for the point L1.

That is where it remains to this day. There is no live feed as Gore had once hoped, but the spacecraft does routinely take photos of the Earth’s surface, perfectly lit by the Sun from behind the camera, which are uploaded by NASA 12–36 hours after they are taken.

The greatest achievement in space in the past few decades has been the construction and operation of the International Space Station in low-Earth orbit. The station has acted as a laboratory to make scientific advances in microgravity and as a testing ground for human survival in potential future colonies on the Moon or Mars. It has also provided a magnificent vantage point from which to view the Earth’s surface.

The results are beautiful.

Follow NASA or ESA on any number of social media platforms and your feed will be awash with stunning images of natural and human-made structures seen from a unique perspective – out the window of the ISS as it flies above us at nearly 8km/s.

I believe that the environmental value of photos of Earth from space now lies in social media. We are very accustomed to seeing such images, so they may not give us pause as they once did, but every single one quite literally gives the viewer a new perspective on their home planet. As photos and videos displaying the diversity and beauty of nature do the rounds on Twitter and Instagram, we see Earth in ways no person could have seen it for the overwhelming majority of human history. It is unlikely I will ever visit the Himalayas, but I have seen Mount Everest rising up out of the clouds in the early morning. I’m not a polar climate scientist, but I have seen the ice caps recede year on year. I don’t live in a wildfire hotspot, but I have seen smoke and flames decimate the world’s forests.

We see Earth in ways no person could have seen it for the overwhelming majority of human history

With that knowledge comes the desire to act, to vote, to donate, to change personal behaviours. Images of our world alone in the darkness show us the vulnerability of life. Images of our world on fire show us the threat that we pose to our own home. Thanks to photos from space, the general public is better informed on the devastation that we are causing to our ecosystems, and better acquainted with the splendour of that which we stand to lose.

This is our only home. Our ability to destroy it is not at all matched by our ability to leave it.

We must do everything in our power to protect it.

____________________

Related post: for more on Lagrangian points and the weird orbital patterns we see in the Solar System because of them, here’s a post I wrote last year on co-orbital configurations.